|  |

|

Camp Chase |

|

|

|

|

|

Camp Chase was one of the five largest prisons in the North for Confederate prisoners of war. Camp Chase's prison population peaked at 9,423 on January 31, 1865. The Army ensured that the graves of those who died were marked with thin headboards and "only the number of the grave and name of its individual occupant;" thus the "graves of the Confederate soldiers were not marked as soldiers, and remained thus inadequately," until the 20th century when Congress approved efforts to recognize the sacrifice of CSA soldiers.¹

The following information is excerpted from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Camp Chase Site, Columbus, Ohio.

Statement of Significance: Camp Chase was officially dedicated June 20, 1861. It is named in honor of Salmon Portland Chase (1808-1873), former governor of Ohio, the Secretary of the Treasury under President Abraham Lincoln, and later Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Initially designated as a training camp for new recruits in the Union Army, Camp Chase was converted to a military prison as the first prisoners of war arrived from western Virginia. In the early months of the Civil War, Camp Chase primarily held political prisoners--judges, legislators and mayors from Kentucky and Virginia accused of loyalty to the Confederacy. In early 1862, Camp Chase served briefly as a prison for Confederate officers. But after a military prison for Confederate officers opened at Johnson's Island, Ohio, Camp Chase housed only non-commissioned officers, enlisted men, and political prisoners.

In February 1862, 800 prisoners of war (officers and enlisted men) arrived at Camp Chase. Included among the 800 Confederate soldiers were approximately 75 African Americans; about half of whom were slaves, the other half being servants to the confederate officers. Much to the horror and dismay of the citizens of Columbus, these men continued to serve their master's in the prison camp. An Ohio Legislative committee was formed and protests over the continued enslavement of these men were sent to Washington D.C. The African Americans were finally released in April and May of 1862; some then enlisted in the Union army.²

According to an exchange agreement reached between North and South on July 22, 1862, Camp Chase was to operate as a way station for the immediate repatriation (return to country of birth or citizenship) of Confederate soldiers. After this agreement was mutually abandoned July 13, 1863, the facility swelled with new prisoners, and military inmates quickly outnumbered political prisoners. By the end of the war, Camp Chase held 26,000 of all 36,000 Confederate POWs retained in Ohio military prisons. Crowded and unhealthy living conditions at Camp Chase took a heavy toll among prisoners. Despite newly constructed barracks in 1864, which raised the prison capacity to 8,000 men, the facility was soon operating well over capacity. Rations for prisoners were reduced in retaliation against alleged mistreatment at Southern POW camps. Many prisoners suffered from malnutrition and died from smallpox, typhoid fever or pneumonia. Others, even those who received meager clothing provisions, suffered from severe exposure during the especially cold winter of 1865. In all, 2,229 soldiers died at Camp Chase by July 5, 1865, when it officially closed.

Original Physical Appearance: The flat, farming land that became Camp Chase was leased to the U.S. Government at the beginning of the Civil War. One hundred sixty houses were built on the site to replace the overflowing barracks at Camp Jackson on the north side of Columbus. When the first prisoners of war arrived, a stockade was built on the southeast corner of the campgrounds. This stockade rested on a half-acre plot and accommodated 450 prisoners in three single-story frame buildings with partitioned rooms and tiered bunks. Two of the buildings measured 100' x 15', and a third measured 70' x 20'. A 12' high plank wall with flanking towers surrounded the stockade, named Prison No. 1. More buildings were added in November 1861 to relieve the critical housing shortage caused by incoming prisoners. Three more 100' x 15' barracks, designated Prison No. 2, were erected on land contiguous to the fist stockade.

As more POWs filled the campgrounds, additional barracks were needed. Prison No. 3, a three-acre tract, was built in March 1862. Huts arranged in clusters of six formed a residential nucleus. Each hut measured 20' x 14'and was made of planks and a light wood frame. The huts were spaced 2 ½ feet apart in each cluster, while series of clusters formed four parallel lines separated by narrow dirt roads. In summer 1864, the huts of Prison No. 3 were demolished to make way for 17 new barracks, each 100' x 22', to accommodate 198 prisoners. Volunteer prison labor built the barracks using lumber from the previously demolished huts.

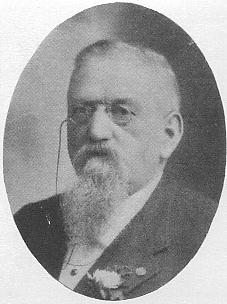

Present Physical Appearance: None of the original Camp Chase (above ground) structures exist today. All were dismantled at the end of the Civil War and the materials were reused. A prison cemetery, established in 1863, occupies less than two acres of the original campgrounds. A stone wall, built in 1921, encloses 2,199 graves of Confederate soldiers who died while POWs. To commemorate these losses, a memorial arch built of granite blocks was unveiled in 1902; it spans a large boulder just 75' inside the Sullivant Avenue entrance to the cemetery. Above the arch rests a bronze statue of a Confederate soldier facing south; the keystone of the arch is inscribed "AMERICANS." Marble headstones, authorized by an Act of Congress in 1906, identify the grave of each soldier. A stone speaker' platform, completed in 1921, stands directly behind the memorial arch along the north wall.  Col. William H. Knauss Col. William H. Knauss

Near the entrance is a stone arch surmounted by a Confederate Soldier Statue. Erection of the monument was made possible by Colonel William H. Knauss, a Union soldier, who contributed considerable money and effort to promote beautification of the cemetery. (http://cumberlandroadproject.com/ohio/columbus-oh-wpa-guide-1940.php)

http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=662

During the course of the Civil War, over two thousand Confederate prisoners died at Camp Chase. Originally, prison officials buried the prisoners in a Columbus city cemetery. In 1863, the prison established its own cemetery, and the bodies already buried in the Columbus cemetery were re-interred in the prison cemetery. Following the war, thirty-one Confederate bodies from Camp Dennison near Cincinnati were moved to the Camp Chase cemetery. this brought the total number of Confederate burials to approximately 2,260.

The text below is taken from Judge D.F. Pugh’s address at the dedication of the Camp Chase Cemetery. He was at the time Past Department Commander of the GAR of Ohio, and spoke respectfully of the valor and dedication of his brave, half-fed and barefooted adversaries from the American South.

Great and Famed American Soldiers

“That the Confederate soldiers were gallant, that they were hard fighters, can be proved by every Union soldier who struggled against them in the fiery front of battle.

After the battle of Missionary Ridge I was attracted by the extreme youthful appearance of a dead Tennessee Confederate soldier who belonged to a regiment of Cheatham’s Division, against which we had fought the day before. He was not over fifteen years of age and very slender. He was clothed in a cotton suit and was barefooted – barefooted!—on that cold and wet 24th day of November, 1863.

I examined his haversack. For a day’s rations there were a handful of black beans, a few slices of sorghum, and a half dozen roasted acorns. That was an infinitely poor outfit for marching and fighting, but that Tennessee soldier had made it answer his purpose. The Confederates who, half fed, looked bravely into our faces for many long, agonizing weeks over the ramparts of Vicksburg; the remnants of Lee’s magnificent army, which, fed on raw corn and persimmons, fluttered their heroic rags and interposed their bodies for a year between Grant’s army and Richmond, only a few miles away – all these men were great soldiers. I pity the American who cannot be proud of their valor and endurance.

We can never challenge the fame of those men whose skill and valor made them the idols of the Confederate army. The fame of Lee, Jackson, the Johnston’s, Gordon, Longstreet, the Hills, Hood and Stuart, and many thousands of noncommissioned and private soldiers of the Confederate armies, whose names are not mentioned on historical pages, can never be tarnished by the carping criticisms of the narrow and shallow-minded.”

(Judge Pugh’s Address, Confederate Veteran, July 1902, page 295)

Some links to Camp Chase POW Camp:

http://www.censusdiggins.com/prison_campchase.html

http://www.lib.lsu.edu/cwc/projects/dbases/chase.htm

http://www.geocities.com/pentagon/quarters/5109/

http://www.forgottenoh.com/Cemeteries/campchase.html

The Story Of Camp Chase -- William H. Knauss

http://books.google.com/books?id=BhYTAAAAYAAJ&dq=The+story+of+Camp+Chase&printsec=frontcover&source

Next Page |

|

|

|

|

|  |  |